Lesson on TATAKalikasan Ateneo de Manila University

87.9 FM Radyo Katipunan, 11 to 12 a,m, Thursday

Forest Cathedral

A tribute to Pamana (Philippine Eagle), a national treasure.

In observance of the Week of the Philippine Eagle (June 4 to 10, 2023),

International DAY OF THE FOREST (March 21) and EARTH Day (April 22)

Part 1 - Philippine Eagle - a national treasure.Part 2 - The Stone EaglePart 3 - Biology of the Philippine EaglePart 4 - Week of the Philippine Eagle (June 4 to 10, 2023)Part 5 - Let Us Save Other Wildlife Species

Dr Abe V Rotor

Co-Host with Prof Emoy Rodolfo

[avrotor.blogspot.com]

Part 1 - Philippine Eagle - a national treasure.

Forest Cathedral in acrylic (30" x 48") by AV Rotor 2015

It is a place where the spirit of a sacred and noble bird* returns to the home of its ancestors and kin and tells the story of man, the rational, the wise, self anointed guardian of creation, yet in many ways cruel, uncaring, and cold;

It is a place where a stream is born from the watershed of trees, shrubs and lianas, gathering rain that falls anytime in the day and night, dewdrops from mist and fog, spring water from aquifers and water stored under the ground;

It is a place where the life-giving sunlight casts over the vast canopy of the forest, seeps through the foliage and nourishes the undergrowth, the epiphytes and lianas, and over the forest floor to wake up the sleeping seeds and spores;

It is a place where the "lungs of the earth" give off oxygen in exchange of carbon dioxide, condenses clouds into rain, keeping the integrity of the water cycle that is vital to all living things, and to our economy, health and welfare;

It is a place where threatened and endangered organisms find refuge, and given time and chance to restore their number into sustaining population levels, e become capable of living again freely and openly with other species;

It is a place where leaves turn gold to orange and red come every fall, showering confetti and building litter on the forest floor, home of a myriad of living minutiae that convert organic materials back into elements for the next generation;

It is a place where new and unknown species have yet to be discovered before they disappear with the destruction of their habitats, where other secrets of nature are revealed, and medicine and other useful materials are developed;

It is a place to see animals otherwise reared as pets or caged in zoos live free: colorful parrots in lovely pairs, flying lemurs glide across treetops, kalaw or hornbill perched on high trees, tigers training their cubs, eagles ruling the sky;

It is a place to listen the sounds of nature traced to different organisms like the shrill of cicada at summer's end, croaking of frogs in the rain, shrieking monkeys at play and abandon, sonorous call of hornbills, slithering sound of reptiles on the move;

It is a place where naturalist Edward O Wilson formulated the principles of socio-biology; where Henry David Thoreau wrote a treatise between man and nature, Walden Pond; where Jean-Henri Fabre studied insects known as entomology;

It is the setting of beautiful stories and music: Francisco Baltazar's Florante at Laura, Jack London's Call of the Wild, Robin Hood, and many stories for children; Beethoven's Pastoral, Mendelssohn's Hebrides Overture, and Jean Sibelius' Tapiola;

It is a place where we pay homage to the home of our ancestors, before they set out onto the grassland where they hunted, and later built communities and institutions leading to the creation of human societies, and ultimately nations. ~

-----------------------------------------

*Lost national treasure, Philippine eagle Pamana (heritage) shot and killed within its sanctuary in Mount Hamiguitan, a UNESCO heritage site on August 16, 2015. It is one of the few remaining members of the species, formerly Philippine monkey-eating eagle.

Details of painting

A pair of parrots

Pamana, the lost Philippine eagle

Young adventurers on a forest stream, a pair of parakeets, a pair of tarsiers

A pair of Philippine deer; a pair of flying lemurs

LESSON on TATAKalikasan Ateneo de Manila University, 87.9 FM Radyo Katipunanan every Thursday 11 to 12 noon (author as co-host)

LESSON on former Paaralang Bayan sa Himpapawid (People's School-on-Air) with Ms Melly C Tenorio 738 DZRB AM Band, 8 to 9 evening class, Monday to Friday [www.pbs.gov.ph]

Part 2 - The Stone Eagle

The stone eagle does not answer,

its world too, is forever gone.

Your wings all day spread and flap,now raised in surrender;And the wind that carried you uphas put you asunder.Majestic and lovely, oh bird,lord of the open skies;Across the islands were heard,your pleas and helpless cries.Would a monument sufficeto enthrone your life and deed,Bestow a posthumous prize,to hide man's folly and greed?The stone bird does not answer;its world too, is forever gone,And man takes pride in his powerof make-believe in his art.~

Endangered living symbol, Philippine Eagle, formerly, Monkey Eating Eagle, is one of the biggest eagles in the world. Photograph by Matthew Marlo R. Rotor, Canon EOS 135, Sigma 70-300 mm 2009

Lord of the sky, king among the feathered, fly -over land and sea and sky;All day long from dawn to dusk over mountains high,in majestic victorious cry;Envy of migrating birds wave after wave passing by,so with the Monarch butterfly;That was before - then the forests touched the sky,but now people just look up and sigh. ~

The Philippine eagle, Pithecophaga jefferyi, also known as the monkey-eating eagle or great Philippine eagle, is a critically endangered species of eagle of the family Accipitridae, Class Aves, which is endemic to forests in the Philippines. This species is endemic and found on only four islands in the Philippines: Leyte, Luzon, Mindanao, and Samar. References: Living with Nature, AVR, UST Manila, Wikipedia, Internet

Part 3 - Biology of the Philippine EaglePhilippine Eagle Foundation Sole Website

Be a friend of the Philippine Eagle, 10 years in review

From the Training Manual on Research and Monitoring Techniques for Birds of Prey in the Philippines.

"On our 35th year of being at the forefront of saving the critically endangered Philippine eagle, we recognize our milestones that advanced our mission. And as we leap forward to many more, we are rallying the Filipino people to join us in saving eagles, protecting forests, and securing our future. Let us celebrate how far we have come in conserving our national bird. It is time to transform awareness into commitment and action that preserve our eagle and our forests." - Philippine Eagle Foundation.

The Philippine Eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi) is a giant forest raptor endemic to the Philippines. It is considered one of the largest and most powerful eagles in the world. Unfortunately, it is also one of the world’s rarest and certainly among its most critical endangered vertebrate species. The eagle is known to be geographically restricted to the islands of Luzon, Samar, Leyte and Mindanao.

A. Breeding Biology

Philippine eagles are monogamous and they bond for life. But contrary to claims that they opt to remain unpaired in the death of their mate, evidences from natural pairing techniques and data from all other raptors indicate that they take in new mates as replacement. Females reach sexual maturity at around five years and males, at seven.

1. Courtship

Increased aerial displays, frequent stay near the nest and nest-building activity mark the start of the courtship period. In a study of a pair in 1999, courtship began as early as July. Aerial displays such as mutual soaring (paired soaring flight over the nesting territory), dive chase (diagonal drop by the female with the male trailing in pursuit), and mutual talon presentation (male extending talons to female’s back with the female flipping over to present its talons) were documented. The pair also performed cruising flights over the territory, and did frequent advertisement displays couple0d with vigorous calling. Delivery of nesting materials, although aimed at building nest, can be a form of display to signal readiness to breed. Repeated copulation on nest and nearby perches marks the peak of courtship. Besides ensuring successful fertilization, frequent copulation is also interpreted as another means to strengthen pair bond.

Although different in few details, the courtship behavior observed in this particular pair is generally similar to most diurnal raptors. Courtship displays are expected to aid in the establishment and defense of a nesting territory, attraction of a suitable mate, and the establishment of a strong pair bond, all which are necessary for successful breeding.

2. Timing of Breeding

Data from nesting pairs in Mindanao suggest that the nesting (egg-laying) season can start in September and may extend up to February of the following year. But in Luzon, it is between mid-December to mid-January. The factors responsible for seasonal timing of breeding are not known. However, rainfall patterns, such as the case in Luzon where the periods from September to November are peak typhoon season thus would not be advantageous for egg-laying, as well as the seasonal abundance of the prey have been suggested as possible environmental factors that trigger breeding. A complete breeding cycle, from courtship until the young eagle leaves the parents’ territory, lasts two years.

3. Egg-laying

Observation of captive females revealed that as egg laying draws near, the female appears to be sickly and would not take food for as long as 8 to 10 days. They have drooping wings, takes up a lot of water, continually do calls and builds nest. This condition is called “egg lethargy”. After this phase, the female lays one egg during the late after noon or at dusk.

4. Incubation, nestling and post-fledgling

For a complete breeding cycle, the females lay only a single egg. But if an egg failed to hatch or the chick died early during the first year, the eagles normally nest the following year. As soon as an egg is laid, the female would start incubating. Consequently, breeding behavior stops but sometimes it may still happen a few days after the egg is laid. It is believed that this is meant to ensure that a new egg gets laid just in case the egg under incubation failed.

Incubation lasts 58 to 68 days. Both the male and the female incubate the egg but the female has a greater share of the daytime, and apparently does all of nighttime, incubation. The female spent about two thirds of the incubation up to the early nestling period. After which, both hunt and feed the growing eaglet until independence. In one nest observed, the adults take turn brooding the young and covering it from the sun and the rain. But this ceased when the chick was left on its own in the nest when it was seven weeks old and thereafter. Once the egg is hatched, the eaglet will stay in the nest or about 5.5 months. The parents will take care of it for about 17 months until it leaves its parents territory in search of a vacant habitat.

Recent detailed observation gave revelations about play behavior in a juvenile Philippine Eagle. It was seen observing tree cavities and grasping the rim of knotholes using its tail as props and wing for balance while poking its head into the cavity. The young eagle also hangs itself upside down perhaps as an exercise in balance and was also seen doing mock attacks of inanimate objects on the ground or among tree crowns. All of these were done in the absence of the parents, which indicate that juveniles seem to learn hunting without parental intervention.

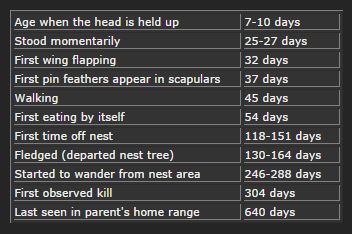

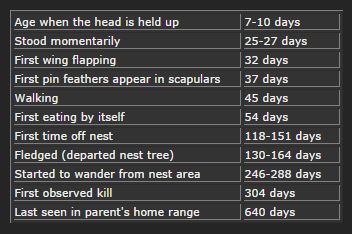

The table below summarizes the patterns of juvenile development as observed by Kennedy (1985).

5. Longevity

Author (right) and house guest Carlo from DSWD hold a mounted head of Philippine Deer*, now listed among the threatened wildlife species. The wooden head is one of a dozen specimens, sculped from actual deer horns, by a local artist and former professor of the University of Northern Philippines, Jose Lazo Jr, (lower photo).

The Philippine Eagle is a long-lived species. A captive bird in Rome Zoo was received full grown in 1934 and died in 1976, making it at least 41 years old at death. A male eaglet at the Philippine Eagle Center arrived as a young bird in 1969 and it’s still alive and that makes it about 34 years old. It is still unknown how old eagles get in the wild. But based on the fact that wild birds face the many exigencies of the forest environment which is rather absent in the captive conditions, wild birds may live shorter than captive birds.

B. Feeding Ecology

The food habits of the Philippine Eagle are known from prey items brought into nests. Studies from 1978 to 1983 revealed that 15 species of vertebrate prey were used for feeding the young including flying lemurs, squirrels, snakes, civets, hornbill, bats and monkeys. But of these prey species, eagles seem to prefer flying lemurs and civets. For the past three decades, only three studies were done on Philippine Eagle breeding and food habits and contrary to persistent claims, no domestic animals were ever brought to nests. The table below shows the list of prey species identified during a study by Kennedy (1985). This table was modified from Kennedy.

The variety and size differences of prey suggest that the Philippine Eagle is an opportunistic hunter with preference for tree-dwelling species. Investigators also suspect that eagles are capable of shifting prey, choice of prey may also coincide with the breeding season of the particular prey.

Observations of their hunting behavior are scant. But more recent detailed observation provided starling revelations. The juvenile learns hunting behavior without parental intervention. Philippine Eagles hunt from perch, constantly observing knotholes or cavities in trees. Adults have been observed to poke their talons into tree cavities to apparently grab prey. One investigator believed that the relatively longer tarsus of the Philippine Eagles is an adaptation to taking prey from tree cavities. But this hypothesis needs further testing.

Meanwhile, the food habits of Philippine Eagles in Luzon have not yet been documented. Because of the difference in terms of the faunal composition of Luzon and Mindanao, them representing different faunal regions, the eagles there would definitely have a different diet regime. For example, flying lemurs, which are the preferred prey in Mindanao, is absent in Luzon. A food habit study in Luzon is long overdue.

C. Regional Breeding Density and Population Estimates

The current population status of the Philippine Eagle is not known. The species has been considered rare since it was discovered in 1896. Moreover, the eagle has always been difficult to census because of the significant logistic difficulties of working in dense, steep rainforest.

Previous attempts to survey or estimate the population status of the species have always been crude at best. Only scattered, individual reports occurred up through the 1960s. Additionally, data from researchers in the 70s to the early 80s were difficult to interpret. And because of the small sample sizes and nature of approaches used, no confidence limits could be established for these estimates. However, based on systematic surveys in the last decade, breeding density estimates suggest there are about 200 pairs in Mindanao. Using the same estimates, about 300 pairs could be present in the other islands where it has been found.

The general indicators of population status continue to be alarming. Habitat and probably prey populations are continuing to disappear at a rapid rate. Thus, wild populations are losing places to live and are likely becoming food-stressed. Hunting and shooting of wild birds also persist. Eagles that were turned over to the Philippine Eagle Center in recent years either had gunshot wounds or were trapped illegally in the wild. Even birds that seemed healthy at the time of recovery or confiscation were found to have airgun pellets in their bodies after undergoing X-ray examinations.

Of the two primary characteristics of populations, i.e. reproductive rate and survival rate, the latter is the most important for populations of long-lived, slowly reproducing species such as the Philippine Eagle. Chance effects (such as weather fluctuations, epidemics, inbreeding, etc.) only make matters worse for small populations.

(From the Training Manual on Research and Monitoring Techniques for Birds of Prey in the Philippines)

D. Habitat Preferences

Except in Mindanao Island, no nest or nest site has ever been studied on other islands within the Philippine eagle’s range. In Mindanao, they are known to nest in a variety of habitats. Some nest on large trees in the lowlands and upper hill dipterocarp forests. Some may even nest at high elevations at transitions to montane or mossy forests. A few nests were in degraded forests near human habitations while others nest within forest interiors. Nest trees are found between 750 to 1590 meters in elevation and they are commonly along steep slopes and ravines, but not necessarily near river systems.

In nest site selection study done in 2001, six characteristics of nest trees seem to be selected for. These are namely height of nest tree, tree density, tree frequency and distance from nearest forest edge, forest trail and kaingin. They also select trees with denser canopies and large trunk spacing. The common Dipterocarp tree species used as nest tree include Shorea almon , S. contorta, S. polysperma, S. negrosensis, whereas the Non-dipterocarps were Balete Ficus sp ., Igem Dacrycarpus imbircatus, and Binuang Octomeles sumatrana. Other nest tree species that has been recorded are Parashorea plicata, Petersianthus quadrialata, and for a for a single record in Luzon, Agathis alba. Eagles don’t seem to prefer specific tree species. Because large trees remain relatively abundant in Mindanao, availability of nesting trees doesn’t seem to limit population there.

Trees towards northern slopes facing the mountain appear to be selected. This might be associated with cooler temperatures, less sunlight, and denser tree cover that increase protection on the nest. Nest trees in Mindanao predominantly have southern exposures (southwest and southeast) and crowns were open enough to facilitate flight to and from the nest.

The nest is normally located between 27 to 50 meters from the ground. They are built on either major branches or tree forks. These nests are large platforms of decaying twigs and sticks that piled atop each other because of the continued nest building and repeated use. Nests are also associated with large epiphytes. A nest could be anywhere between1.2 x 1.2 meters to 1.2 x 2.7 meters in size. ~

Part 4 - Week of the Philippine Eagle (June 4 to 10, 2023)

From National Today (Internet)

The Week of the Philippine eagle is celebrated from June 4 to June 10 every year. It is a week dedicated to celebrating one of the special creatures in the world, the Philippine eagle.

The Philippine eagle is also known as the monkey-eating eagle and is a critically endangered species. It can be found in forests in the Philippines. It has brown and white-colored plumage, a shaggy crest, measures between 2.82 to 3.35 feet in length, and weighs about 8.98 to 17.6 pounds. As this species is rare and endangered, it is important to set measures to preserve them and educate the public about them so we can have more generations of these special birds.

HISTORY OF WEEK OF THE PHILIPPINE EAGLE

The Philippine Eagle was first studied in 1896 by English explorer and naturalist, John Whitehead. He observed the bird alongside his servant and collected the first specimen. He then sent the skin of the bird to William Robert Ogilvie-Grant in London that same year. Robert showed it off in a local restaurant and moved on to describe the species a few weeks later.

After its discovery, the Philippine Eagle was called the ‘monkey-eating eagle’ as there were reports from the natives of Samar and Bonga, the eagle’s place of discovery, that it preyed exclusively on monkeys. It gave rise to the Philippine eagle’s generic name which stems from the Greek word ‘pithecus,’ meaning ‘ape or monkey,’ and ‘phagus’ meaning ‘eater of.’ The species’ name is derived from Jeffery Whitehead, the father of John Whitehead. After some time, studies began to reveal that the monkey-eating eagle ate other animals like large snakes, monitor lizards, and some large birds. The name ‘Philippine eagle’ was officially given to the animal by presidential proclamation in 1978 and it was declared a national emblem in 1995.

In terms of length and wing surface, the Philippine eagle is considered the largest of the extant eagle species. The Harpy eagle and the Steller’s sea eagle are larger in terms of bulk and weight. The Philippine eagle is now endangered due to hunting and the loss of its habitat due to deforestation. To combat this, the Philippines government banned the killing of the Philippine eagle and it is punishable by 12 years imprisonment and heavy fines. Not just the Philippines, but the world at large should join together to preserve the Philippine eagle for future generations.

WEEK OF THE PHILIPPINE EAGLE TIMELINE

- 1896 Discovery. The Philippine eagle is first studied by English explorer and naturalist, John Whitehead.

- 1919 Further Studies. The skeletal features of the Philippine eagle are studied.

- 1978 Official Naming. The name ‘Philippine eagle’ is officially given to the animal by presidential proclamation.

- 1995 National Emblem. The Philippine eagle becomes a national emblem.

WEEK OF THE PHILIPPINE EAGLE FAQS

- How many Philippine eagles are left? There are less than 400 breeding pairs left.

- What is the significance of the Philippine eagle? It represents the bravery and strength of the Filipino people.

- How much weight can the Philippine Eagle carry? Most of them can carry anything from five to six pounds from flat ground.

HOW TO OBSERVE WEEK OF THE PHILIPPINE EAGLE

- Advocate against deforestation

- Advocate against deforestation not just during the week but throughout the year. It affects the animal in their local environment as they become displaced when they lose their habitat.

- Spread awareness

- Celebrate the day by spreading awareness. Lots of people, especially those living outside the Philippines don’t know about the week and so it presents a good opportunity to introduce them to the Philippines eagle.

5 FACTS ABOUT THE PHILIPPINE EAGLE

- It has a long lifespan

- The Philippine eagle has a long lifespan as it can live up to 60 years.

- Females are bigger. The female of the species is usually bigger than the males.

- They have a distinguished noise. Philippine eagles have a loud and high-pitched noise to show their fierceness and territorial nature.

- They have clearer eyesight than humans. Philippine eagles can see about eight times farther than humans.

- They are monogamous. The Philippine eagle sticks with one partner all its life.

WHY WEEK OF THE PHILIPPINE EAGLE IS IMPORTANT

- It preserves the Philippine eagle

- As the Philippine eagle is an endangered species, celebrating the week draws us closer to finding ways to ensure their survival. This is a positive development for a truly magnificent animal.

- It brings more attention to the Philippine eagle

- Not everyone knows about the Philippine eagle and so the week brings more eyes to them. People get to find out about them during the week.

- It discourages uncontrolled deforestation

- The week discourages uncontrolled deforestation. This isn’t just good for the Philippine eagle, but for other animals and for the safety of the world as well.

Acknowledgement: Philippine Eagle Foundation; Ateneo de Manila University

87.9 FM Radyo Katipunan; National Today, Internet

Part 5 - Let Us Save Other Wildlife Species

Dr Abe V Rotor

Author visits sculptor Jun Lazo at his shop in San Vicente IS. Mounted specimen

are on display at the Living with Nature Center, San Vicente, Ilocos Sur.

A wall mural of a family of deer amuses a neighborly lass at the author's

city residence in QC.

Other endangered animals in the Philippines

- Philippine Tarsier (Tarsius syrichta)

- Philippine Spotted Deer (Cervus alfredi)

- Writhed-billed Hornbill (Aceros waldeni)

- Sulu Hornbill (Anthracoceros montani)

- Tamaraw (Bubalus mindorensis)

- Philippine Bare-backed Fruit Bat (Dobsonia chapmani)

- Mindoro Bleeding-heart (Gallicolumba platenae)

- Philippine Eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi)

- Negros Fruit Dove (Ptilinopus arcanus)

- Flame-breasted Fruit Dove (Ptilinopus marchei)

- Visayan Warty Pig (Sus cebifrons)

- Philippine Freshwater Crocodile (Crocodylus mindorensis)

- Giant Clams (Tridacna spp. and Hippopus hippopus)

- Cebu Flowerpecker (Dicaeum quadricolor)

- Tarsier, the smallest primate, found in Bohol (Carlito syrichta)

Flying Lemur and Tamaraw, found mainly in Mindanao

and Mindoro Island, respectively.

Other Endangered Species in Other Parts of the World

Siberian Tiger, so with the Bengal Tiger

American (California) Condor; Lemur, so with our local flying lemur

Arowana, so with the Arapaima; right, Sea Otter

A huge pile of bison skull - a case of species annihilation led by

the legendary Buffalo Bill in the pioneer era of the USA.

Critically Endangered. 3079 animals and 2655 plants are Endangered worldwide, compared with 1998 levels of 1102 and 1197, respectively

*The Philippine deer (Rusa marianna), also known as the Philippine sambar or Philippine brown deer, is endemic to the Philippines. It grows to 1.3 meters and 49 kg when mature. It belongs to Family Cervidae.

Acknowledgement: Internet, Wikipedia

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment