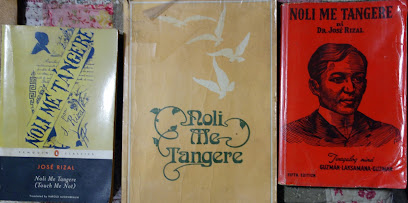

Dedicated to our country's National Hero, born June 19, 1861, and whose martyrdom on December 30, 1896 ignited a revolution against Spain leading ultimately to Philippine Independence.

Rizal: boy and man; Artist's study: head profile of Rizal

Rizal as a student in Europe; right, most popular portrait, in official documents and books; Rizal, had he reached 90. Acknowledgment: Mr. Philip Cabrera, son of the artist; and the National Historical Institute.

This article serves as a reference guide to students taking the Rizal Course, a three-unit subject in college.

Dr Abe V Rotor

Former Professor, Rizal Course, UST and SPUQC

Living with Nature School on Blog

The following article about Dr Jose Rizal is widely circulated on the Internet in celebration of Rizal Day which is observed every 30th day of December, the day he was executed in Bagumbayan by Spanish authorities. To preserve the originality of the report, I am presenting it the same way it is found on the Internet and as written by two sources of information, for which I express my indebtedness and gratitude. Rizal as the Father of Filipino Nationalism (Manila: Bureau of printing, 1941), pp.3-4.; and Rizal's Concept of World Brotherhood, 1958, pp.48-60. The intention of printing this article about Dr. Rizal, is to provide a fresh perspective about him and his teachings - and principally for the cause for which he gave his life - a cause which we would like to review in the light of present problems and challenges. - AVR

TRIVIA: Complete name of Jose Rizal: José Protasio Rizal Mercado y Alonso Realonda

The Philippine national hero, Jose Rizal, has his own views and concepts about Global Fellowship which is synonymous to "Internationalism", "Worldwide Brotherhood", "International Alliance", and "Global Fellowship of Humankind". The following concepts are taken from Rizal's own words, speeches, literature, and careful analysis of his personal history and works.

"It is not what your country can do for you, but it is what you can do for your country." -Rizal

Factors that shaped Rizal

Among the factors that shaped Jose Rizal as a person:

1. Racial origin: Rizal descended from the Malay race and also genetically inherited the mixed Ilocano and Pangasinan bloodline of his mother. He also has Chinese and Spanish lineage.

2. Faith (religion): Christianity also shaped Rizal's way of thinking. He was born, baptized, and raised as a Roman Catholic.

3. His being a reader of books: He read many manuscripts, books, and other publications printed in various languages.

4. His being a linguist: His knowledge of different languages apart from his own. He can speak and understand 22 languages.

5. His voyages: He was able to befriend foreigners from the various nations that he was able to visit.

Rizal's ideas about "Brotherhood" (Fellowship)

These are Rizal's ideas about the subject of having a fellowship or brotherhood of humankind:

1. Education: The proper upbringing and education of children and daughter in order for them to prevent the same fate and suffering experienced by the uneducated and ignorant fellowmen under the rule of the Spaniards.

2. Faith or religion: The belief in only one God. The existence of different religions should not be the cause of misunderstandings. Instead, this existence of many religions should be used to attain unity and freedom. There should be deep respect to every individual's faith; the beliefs that one had become accustomed to and was brought up with since childhood.

3. Fellowman: It is important for one person to have a friend (fellow) and the establishment of an acquaintance with fellow human beings. (It is also important) to recognize the equality of rights of every fellow human being regardless of differences in beliefs and social status.

Rizal's efforts to promote a "Global Fellowship"

Rizal promoted global fellowship through the following:

a. Formation of organizations: Included here are known scholars and scientists recognized as the International Association of Filipinologists.

b. Friendship: In every journey, he was able to meet and befriend foreigners who sympathize with the experiences and events occurring in the Philippines.

c. Maintenance of communication: Before and during his exile at Dapitan, Rizal was able to keep in touch with his friends located in different parts of the world. He was also able to exchange opinions, writings and even specimens which he then studied and examined.

d. Joining organizations: Rizal believed in the goals of organizations that are related to the achievement of unity and freedom of humankind. He always had the time and opportunity to join into organizations.

Basis of "Worldwide Brotherhood" (Worldwide Fellowship)

These are the basis of the above ideas, which were then taken from Rizal's opinions found in his own writings and speeches which intend to establish unity, harmony, alliance and bonding among nations: The fundamental cause or reason for having the absence of human rights is eradicated through the establishment of unity.

One of Rizal's wishes is the presence of equal rights, justice, dignity, and peace. The basis for the unity of mankind is religion and the "Lord of Creations"; because a mutual alliance that yearns to provide a large scope of respect in human faith is needed, despite of our differences in race, education, and age. One of the negative effects of colonialism is racial discrimination. The presence of a worldwide alliance intends to eradicate any form of discrimination based on race, status in life, or religion.

Rizal wishes Peace to become an instrument that will stop the colonialism (colonization) of nations. This is also one of Rizal's concerns related to the "mutual understanding" expected from Spain but also from other countries. Similar to Rizal's protest against the public presentation (the use as exhibits) of the Igorots in Madrid in 1887 which, according to him, caused anger and misunderstanding from people who believed in the importance of one's race.

Hindrances towards the achievement of a "Worldwide Brotherhood"

However, Rizal also knew that there are hindrances in achieving such a worldwide fellowship: Change and harmony can be achieved through the presence of unity among fellowmen (which is) the belief in one's rights, dignity, human worth, and in the equality of rights between genders and among nations.

From one of the speeches of Rizal:

“The Philippines will remain one with Spain if the laws are observed and carried out (in the Philippines), if the Philippine civilization is "given life" (enlivened), and if human rights will be respected and will be provided without any tarnish and forms of deceitfulness.”

Rizal's words revealed the hindrances against an aspired unity of humankind:

1. The absence of human rights.

2. Wrong beliefs in the implementation of agreements.

3. Taking advantage of other people.

4. Ignoring (not willing to hear) the wishes of the people.

5. Racial discrimination.

Excerpt from one of Rizal's letter to a friend:

“ If Spain does not wish to be a friend or brother to the Philippines, strongly the Philippines does not wish to be either. What is requested are kindness, the much-awaited justice, and not pity from Spain. If the conquering of a nation will result to its hardship, it is better to leave it and grant it its independence. ”

This letter presents Rizal's desire and anticipated friendship between Spain and the Philippines, but one which is based on equality of rights.

Translation:

"What? Does no Caesar, does no Achilles appear on your stage now,

Not an Andromache e'en, not an Orestes, my friend?"

"No! there is naught to be seen there but parsons, and syndics of commerce,

Secretaries perchance, ensigns, and majors of horse."

"But, my good friend, pray tell me, what can such people e'er meet with

That can be truly great? - what that is great can they do?"

- Friedrich Schiller, "Shakespeare's Ghost," translated by John Bowring

Translation:

TO MY COUNTRY

Recorded in the history of human suffering are cancers of such malignant character that even minor contact aggravates them, endangering overwhelming pain. How often, in the midst of modern civilizations have I wanted to bring you into the discussion, sometimes to recall these memories, sometimes to compare you to other countries, so often that your beloved image became to me like a social cancer.

Therefore, because I desire your good health, which is indeed all of ours, and because I seek better stewardship for you, I will do with you what the ancients did with their infirmed: they placed them on the steps of their temples so that each in his own way could invoke a divinity that might offer a cure.

With that in mind, I will try to reproduce your current condition faithfully, without prejudice; I will lift the veil hiding your ills, and sacrifice everything to truth, even my own pride, since, as your son, I, too, suffer your defects and shortcomings.~

NOTE: This article serves as a general reference, and reference to students taking the Rizal Course, a 3-unit subject in college. x x x

-----

Anecdotes about Rizal

Acknowledgement: Internet

1. One day, intending to cross Laguna de Bay, the boy Rizal rode on a boat. While in the middle of the lake, he accidentally dropped one of his slippers into the rough waters. The slipper was immediately swept away by the swift strong currents .Do you know what he did? He intentionally dropped the other slipper into the water. When somebody asked why he did such a thing, he remarked, "A slipper would be useless without its mate".

2. It was Jose Rizal's Mother who told him about the story of the moth. One night, her mother noticed that Rizal was not paying anymore attention to what she is saying. As she was staring at Rizal, he then was staring at the moth flying around the lamp. She then told Rizal about the story related to it.

There was a Mother and son Moth flying around the light of a candle. The Mother moth told her son not to go near the light because that was a fire and it could kill him easily. The son agreed. But he thought to himself that his mother was selfish because she doesn't want him to experience the kind of warmth that the light had given her. Then the son moth flew nearer. Soon, the wind blew the light of the candle and it reached the wings of the son moth and he died.

Rizal's mother told him that if the son moth only listened to what his Mother said, then he wouldn't be killed by that fire.

Rizal must have remembered his mother's anecdote that night a moth visited him in Fort Santiago where he awaited his execution the following morning. He must have thought of the moth dying for his country's freedom. It died for a cause. It is the way martyrs die.

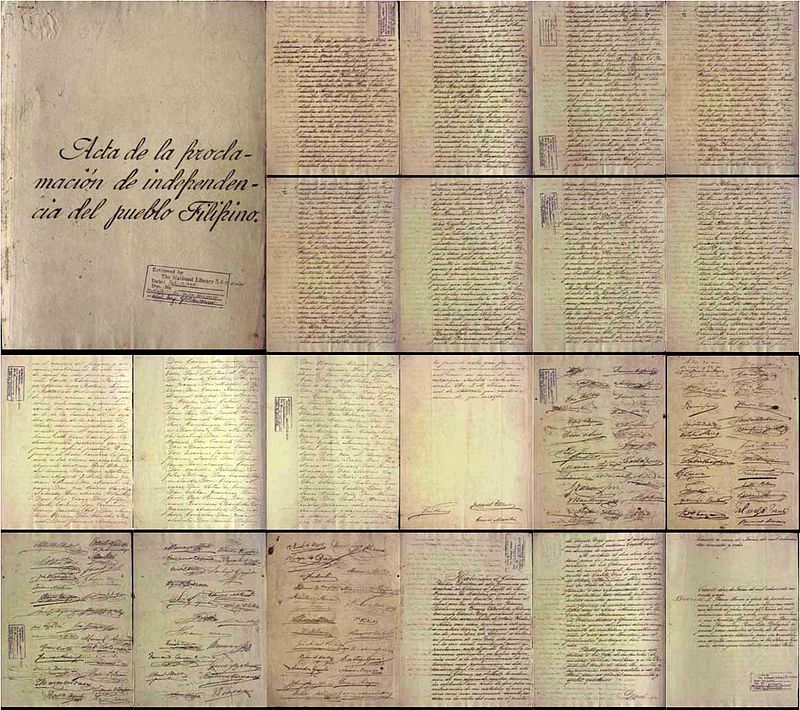

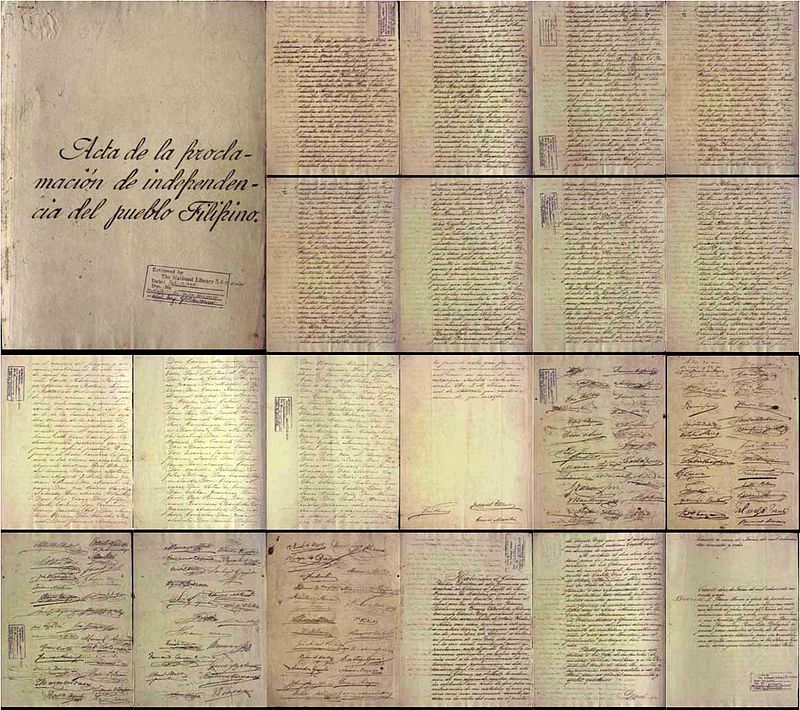

Documents of the Declaration of Philippine Independence on June 1, 1898

Artist's interpretation on Rizal on his way to execution at Bagumbayan. Note lively gait and stride, and apparently jovial conversation with the escorting military officer. It was reported by an attending doctor that Rizal's pulse rate was normal even as he faced the firing squad. BELOW, Original Rizal'a grave.

Artist's interpretation on Rizal on his way to execution at Bagumbayan. Note lively gait and stride, and apparently jovial conversation with the escorting military officer. It was reported by an attending doctor that Rizal's pulse rate was normal even as he faced the firing squad. BELOW, Original Rizal'a grave.

Part 2 - Rizal in Exile at Dapitan

In July 1892, Rizal Arrived in Dapitan as a prisoner. Together with his friend Father Sanchez (PHOTO) he help remake the plaza, and place lampposts at every corner this is Dapitan’s first lighting System.

Delighted at this new life, Commandant Carnicero wrote the Governor General if possible to send for the new plaza twenty-four iron benches and twenty-six hundred meters of wire.

Rizal spent many months draining swamps to get rid of the malaria which infested the region. He directed the construction of a water system for Dapitan.

Rizal's House at Dapitan

It happened that a lottery ticket which he had purchased brought him a prize of six thousand pesos, all of which he spent in Dapitan. He bought sixteen hectares of land along the bay a few hundred meters east of the town of Dapitan and here built himself a little house.

Rizal's Workshop for his students

He wrote to his brother-in-law Manuel Hidalgo, "You can come here and have a big hacienda. . . The government is going to grant three months exemption from service, and a personal loan to all who will come to our colony. All the people of Calamba, Tanawana, Lipa, and etc. can come with their implements. We will establish a new Calamba!“ Thrilled by the dream of having his family and townsmen near him, José planted many coffee and cacao plants and from 800 to 1000 coconuts.

Rizal Cottage in Dapitan; Rizal's ancestral house in Calamba, Laguna

In 1893 Rizal established a school. It began with three pupils and in time increase to 16. his pupils didn't pay any tuition. Instead of charging them tuition fees, he made them work in his garden, fields and construction projects in the community.

Rizal taught his boys reading, writing, languages (Spanish and English), geography, history, mathematics (arithmetic and geometry), industrial work, nature study, morals and gymnastics. He trained them how to collect specimens of plants and animals, to love work, and to "behave-like men."

Rizal's Clinic

As a physician, Rizal became interested in local medicine and in the use of medicinal plants. He studied the medicinal plants of the Philippines and their curative values. To poor patients, who could not afford to buy imported medicine, he prescribed the local medicinal plants. Rizal cared for the sick of Dapitan without ever accepting a fee. People began to come to him from a distance, and these he charged according to their financial circumstances. One Englishman of wealth had cataracts removed from his eyes, and paid 500.00. This money Rizal used for lamps for the Dapitan streets. He had a hospital opposite the house where he dwelt. The adoring people of Dapitan saluted him with more reverence than they showed the Commandant. As a physician, Rizal became interested in local medicine and in the use of medicinal plants. He studied the medicinal plants of the Philippines and their curative values. To poor patients, who could not afford to buy imported medicine, he prescribed the local medicinal plants.

Rizal's mother in Dapitan

Rizal's mother in Dapitan

On August 26, 1893, Trinidad and José's mother left Hong Kong and proceeded to Dapitan where they spent the next eighteen months with José. He gave his mother's eyes the final treatment needed to restore their sight, so that she was able to see the rest of her life. She returned to Manila in February, 1895.

José wrote another poem, in response to a request from his mother, who had all his life, stimulated his poetry. This poem is regarded by some of his admirers as the most profound and noble poem he ever composed. All critics agree that it is second only to "My Last Farewell". This he sent to his mother on October 22, 1895.

In August Leonora Rivera Rizal’s old sweetheart died in Manila, August 28,1893, at the birth of her only son. When he heard of her death, his heart felt a great aching void.

Rizal's Patient

One of Rizal’s patient was a blind American engineer named Taufer, who for years had resided in Hong Kong. He reached Dapitan in February, 1895. With him came her young adopted daughter Miss Josephine Leopoldine Bracken.

Josephine Bracken

Josephine was eighteen, slender, a chestnut blond, with blue eyes, dressed with elegant simplicity. Rizal found this fun-loving girl extremely attractive in his melancholy and intolerably lonely state of mind. she seemed more in love with the great doctor. Within a month they were engaged to be married, and asked Father Obach, the Dapitan priest, to marry them.

But when the blind Taufer heard of the proposed marriage he went into a fearful rage and was prevented from cutting his own throat only when Rizal grabbed and held both his wrists. He and his wife had taken Josephine when her Irish mother died in childbirth, and after Mrs. Taufer died he had depended upon her help during his blind years. The thought of losing the only help he had drove him temporarily insane. To avoid a tragedy, Josephine went off to Manila with Taufer by the first boat.

Acknowledgement:

Sources:

´http://dipologcity.com/AttractionsRizal'sExile.htm

´http://www.joserizal.ph/dp01.html

Part 3 - Rizal as Zoologist and Agriculturist

As a zoologist, Rizal discovered living organisms unnamed in his time, such as a flying (gliding) lizard (Draco Rizali), Harlequin Tree Frog (Racophorus Rizali), among others, named after him. (Reference: Internet)

Rizal as Agriculturist -Jose Rizal’s contribution to the development of Philippine agriculture

Published December 30, 2021, 10:00 AM (From Internet)

by Patricia Bianca Taculao Manila Bulletin

The name Jose Rizal is unlikely to be forgotten in Philippine history books. He has been instrumental in the Filipino’s bid towards independence and several developments in various sectors. Rizal also made contributions to Philippine art, literature, and medicine, which continues to fascinate his countrymen today.

Rizal's shrine at Dapitan

Rizal’s love for the Philippines was evident in nearly all his actions. He was eventually named a national hero because of his efforts, especially his peaceful approach to demanding political reform from the oppressive Spanish rule. Aside from dabbling in the different fields of science, Rizal also showed an interest in agriculture.

Eufemio O. Agbayani III, historic sites development officer of the Historic Sites and Education Division for the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP), shares that Rizal’s early exposure to farming played a role in this.

The national hero came from a family who rented land from the Dominicans to plant sugar, a profitable crop at the time. His family experiences allowed him a glimpse of a farmer’s life. Rizal, at some point in his life, was also encouraged to become a licensed land surveyor.

Although Rizal was attracted to medicine, he also had an early interest in agriculture. There’s even a record of how he lamented to his parents on the lack of individuals who wanted to become experts in the field. And as he ventured abroad to further his studies, Rizal would send back names of books that he thought would benefit Philippine agriculture.

One book that he recommended through a postcard was of John Walker titled “Farming to Profit in Modern Times.” This demonstrated how deeply he considered the success of Filipino farmers by offering them solutions on how growing food can be profitable.

Rizal would also express his regard for Philippine agriculture through the pages of La Solidaridad. In an article for the publication, he explained that Spanish officials burden Filipino farmers instead of supporting them, resulting in low crop production.

Aside from being vocal about his support for Philippine agriculture, Rizal also walked the talk. According to Agbayani, after Rizal’s family was ejected from the Dominican estate they were tenants of in 1891, he planned to establish a new agricultural colony in Sandakan, North Borneo.

Another key example would be during his exile in Dapitan. Just a month into his exile, Rizal began planting fruit trees off the coast. Fate would give him a chance to better experience his farming dream when he won the lottery and used the money to purchase a parcel of land in Talisay where he built his estate.

When Rizal first went to his newly acquired estate, he saw plants growing in the surroundings. He later discovered that these were abandoned by the previous owners because the wildlife kept eating their produce. But this didn’t deter him from growing plants.

Rizal would later share with his family that his Talisay estate has 50 lanzones trees, 20 mango trees, 50 langka trees, 18 mangosteen trees, 16 coconut trees, and several others of makopa and santol. He would eventually plant coffee, cacao, pineapple, and corn.

As Rizal established rapport in Dapitan, locals and indigenous Subanen also helped him establish the estate. Agbayani said that it’s most likely that Rizal’s farming initiative became successful with the help of the local’s knowledge.

Grateful for the help from the locals, Rizal proceeded to establish a water system on his estate, which provided his plants with irrigation and the community with a source of clean water.

The national hero, according to Agbayani, was a profit-minded person, but not in terms of monetary gain. His initiatives were implemented because they benefited him as they kept him independent from Spanish provisions and made the lives of those around him better.

Farming wasn’t Rizal’s sole interest while he was exiled in Dapitan. He entered a partnership with Antonio Miranda, a Spaniard, to improve the fishing industry in the region. Rizal planned to introduce the pukutan (ring net) system but delays prevented one pukutan and two expert fishermen from arriving in Dapitan.

Arrival of Rizal at Dapitan

Rizal was hailed as the Philippine national hero for his peaceful yet powerful approach in demanding government reform from the Spaniards, but his contributions to the Philippines go beyond the political scene. Although inclined towards the arts and sciences, Rizal was also exposed to the life of a farmer, which made him realize the potential of the Philippine agricultural industry if given proper support.

Years later, Rizal’s efforts in intensifying the country’s agricultural industry have been realized by many others who continue to pursue the development that he has been pushing for before.

Acknowledgement: Patricia Bianca Taculao, Manila Bulletin; the Internet ~

Part 4 - Dr Jose P Rizal: Boy and Man

Dr Abe V Rotor

Rizal is not only a foremost nationalist, but a naturalist as well. He probed his being an ecologist, a term coined only in recent times, when he was exiled in Dapitan, an extreme rural place near Ozamis today. Here he founded a village school for children, introduced new methods of farming, planted trees, discovered new organisms, four of them were named in his honor.

Rizal: boy and man

Here are sketches and portraits of Rizal discovered from very old files. On display at the author's residence in San Vicente Ilocos Sur - Heritage Zone of the North (RA 11645)

Artist's interpretation on Rizal on his way to execution at Bagumbayan. Note lively gait and stride, and apparently jovial conversation with the escorting military officer. It was reported

by an attending doctor that Rizal's pulse rate was normal even as he faced the firing squad.

Artist Cabrera's study: head profile of Rizal

Rizal as a student in Europe; most popular portrait in official documents and books; Rizal, had he reached 90. ~

Acknowledgment: Mr. Philip Cabrera, son of the artist; and National Historical Institute.

Part 5 - Rizal's "My Last Farewell" speaks of Nature and Nurture

"My Last Farewell" - Jose Rizal’s Valedictory Poem

Living with Nature School on Blog

On the way to execution by musketry of Dr Jose P Rizal, Philippine National Hero,

on December 30, 1896, at Bagumbayan, now Rizal Park ( Luneta), Manila .

Acknowledgement with Gratitude to source of photo.

"My Last Farewell"

By Nick Joaquin

Translated from the Spanish

Notes on Rizal’s Farewell Poem.

A few days before his execution, Rizal wrote this touching poem in Spanish. He wrote it with no trembling hands; no erasures. The hero wrote on a commercial blue-lined paper measuring 9.5 cm wide and 15.5 cm long. The poem is untitled, undated and unsigned. Rizal hid it inside an alcohol stove he was using. In the afternoon of December 29, 1896, Rizal gave this alcohol stove as a gift to his younger sister Trinidad and whispered: “There is something inside.”

After the hero’s execution, Josephine Bracken got hold of the poem and brought it with her to Hong Kong. She sold it to an American who brought it to the US. In 1908, the US War Department informed the Philippine Gov. Gen. James Smith who instructed the Philippine Government to buy it back. The poem has been translated into practically all major languages of the world, and in many dialects.

.jpg)

.jpg)