The reasons I write

Series of Lectures before graduate students at University of Santo Tomas, De La Salle University (D), and University of Perpetual Help (R) based on Living with Folk Wisdom.Dr Abe V. Rotor

0080.JPG) Published by University of Santo Tomas, launched 2008 Manila International Book Fair, SMX Mall of Asia, 220 pp. "The book is a compendium of indigenous technical knowledge complemented with modern scientific thinking. The narratives offer an exploration into the world of ethno-science covering a wide range of practical interest from climate to agriculture; medicine to food and nutrition..: (Excerpt of Foreword by Dr Lilian J Sison, dean UST Graduate School).

Published by University of Santo Tomas, launched 2008 Manila International Book Fair, SMX Mall of Asia, 220 pp. "The book is a compendium of indigenous technical knowledge complemented with modern scientific thinking. The narratives offer an exploration into the world of ethno-science covering a wide range of practical interest from climate to agriculture; medicine to food and nutrition..: (Excerpt of Foreword by Dr Lilian J Sison, dean UST Graduate School).

" For the science educator and communicator, here is a handy volume to help you reach the popular consciousness. You will find here more than ample number of examples for making connections between lived experience and scientific information." (Dr Florentino H Hornedo, UNESCO Commissioner)

My friends would exclaim and even if they don’t, I could read their eyes. “Why you are still alive!” And I would return a wide grim. And we rejoice. There are many things in this world to be happy about and rejoice.

Eighteen years ago today I was dying in a hospital. After two major operations, I left everything to Providence. I was supposed to deliver a response being an author of a book published by UST, Light from the Old Arch. My daughter Anna stood before the audience on that occasion and gave the response on my behalf. It could not have been any better if I did. She is a brave daughter, and I believed she was guided by the Light I saw and wrote about – Light from the Old Arch.

And so, since that day eighteen years ago, and everyday thereafter I would rise before the sun does, and write my thoughts in the creeping light of dawn. Thoughts come beautifully in the morning of a new day, which I simply call a “bonus” – a term I couldn’t define, much less understand. Every morning is a beautiful morning, and there is nothing more beautiful than it because it is a bonus of an extended life. It is an extension of a breathing, thinking and feeling soul. Above all it is a bonus of thanksgiving.

It was only then that I began to understand who and what is a writer, but why should one write remained elusive, beyond my understanding. I have read about Scheherazade the story teller of "a thousand and one nights," I have read a part of the book Walden Pond of Henry David Thoreau who wrote it far away from society. Or the Brownings in their exchange of romantic feelings in classical poetry. How powerful are the themes of Ernest Hemingway, and I did not expect how his life was ended had I not read what Van Gogh did when he had painted everything, except death. Hellen Keller wrote in the light of darkness because she was blind. So with John Milton who wrote Paradise Lost, and later Paradise Regained when he was already blind. How could Rachel Carson had written if she didn’t see Nature like a woman being raped and trampled?

Before I simply wrote. I looked on all sides for what every event or action there was. Until I saw a dim light coming from the window of an old house. I traced it. It was far and dim yet penetrating in the mist of time, and obscured by the passing views of change.

But it is almost magic. It’s a miracle, if I would say so, because I am still alive today. Thought after thought, page after page, chapter after chapter I was able to write a book, and another. And another that my alma mater, and the UST Publishing House are launching with other new books.

I write because I believe in Robert Ruark’s Something of Value . He said

“If a man does away with his traditional way of living and throws away his good customs, he had better first make certain that he has something of value to replace them.”

· I write because I believe in Lola Basiang relating folklore to children. We imagine a campfire, around it our ancestors exchanged knowledge and recounted experiences, with spices of imagination and superstition. It was a prototype open university. Throughout the ages and countless generations a wealth of native knowledge and folk wisdom accumulated but not much of it has survived.

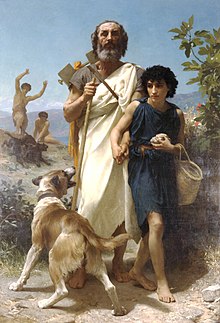

. I write because I believe in Homer’s epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, which in the same way as Aesop’s fables, survived after two or three thousand years.

Homer and His Guide, by William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825–1905), portraying Homer on Mount Ida, beset by dogs and guided by the goatherder Glaucus (as told in Pseudo-Herodotus)

· I write because I would not look farther than the timelessness of Christ lessons in parables? The Sermon on the Mount, The Prodigal Son, the Sower, The Good Samaritan - these and many more, continue to live in the home, school, pulpit as it had persisted in the catacombs in the beginnings of Christianity.

· I write because Homer, Socrates, Aesop, Buddha, Christ and other early authors did not write. I am the lesser teacher so that I will enshrine the teachings of these great teachers. I am aware that it is through oral history, in spite of its limitations and informal nature that these masterpieces were preserved and transcended to us - thanks to our ancestors, and to tradition itself.

· I write because I am one of those who inherited and benefit today of the valuable basic scientific knowledge such as the Pythagorean Theorem (all philosophies are resolved into the relations of numbers), the Law of Buoyancy from Archimedes, the Ptolemaic concept of the universe (although it was later corrected with the Copernican model), Natural Philosophy of Aristotle (Natural History), not to mention the Hippocratic Oath, the ethics that guide those in the practice of medicine which our modern doctors adhere to this day.

· I write about Tradition and Heritage. Just as the Egyptians, Greeks, Romans – and even the remote and lesser ancient civilizations like the Aztecs and the Mayas had their own cultural heritage, so have we in our humble ways. Panday Pira attests to early warfare technology, the Code of Kalantiao, an early codification of law and order, the Herbolario, who to the present is looked upon with authority as the village doctor. And of course, we should not fail to mention the greatest manifestation of our architectural genius and grandiose aesthetic sense – the Banawe Rice Terraces. (photo left)

. I write for adventure because I was a boy once upon a time, and the Little Prince in me refuses to grow old. On my part, like other boys in my time, boyhood could not have been spent in any better way without the science fictions of Jules Vernes – Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Eighty Days Around the World – and the adventures of Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. It is the universality of human thoughts and values that is the key to the timelessness of tradition – indeed the classical test of true masterpieces.

· I write about children’s stories. I can only wonder with awe at the determination of the Grimm Brothers roaming the villages of Europe soon after the Dark Ages began to end, and the light of learning began to dawn again, the two scholars retrieving the fragments and remnants of stories surviving the darkest period of history of mankind. And what do we know? These stories, together with the stories from the 1001 Arabian Nights, and Hans Christian Anderson have kept the flame of human hope and joy alive in cradles, around the hearth, at the bedside – even as the world was uncertain and unkind.

. I write because I often ask myself if it is only truth that can withstand the test of time. Or, if only events that really happened constitute history. And if there were any tinge that these stories were based on the culture of a people in their own time, would we not find them, we who live on the other side of the globe and in another time?

· I write to explore and retrieve traditional knowledge from records of the past, archaeology, and testimonies of old folks. It is indeed an enormous task not only what but how we can gather the fragments of knowledge, distinguish facts from myths, reality from imagination, and draw out the threads of wisdom and weave them into a fabric we call science. Today with modern science and technology, we create virtual reality scenarios on the screen and in dioramas, reliving the past and deliver them right in the living room and in the school.

· I write to rediscover indigenous knowledge and folk wisdom which enlarges and enhances our history and tradition. Even beliefs and practices, which we may not be able to explain scientifically, can be potential materials for research. And if in our judgment they fail to meet such test, still they are valuable to us because they are part of our culture and they contribute immensely to the quaintness of living.

· I write because I am inspired by the beautiful novel Swiss Family Robinson written by Johann Wyss nearly two centuries ago. It is about a family stranded in an unknown island somewhere near New Guinea and during the many years they lived in the island, they learned to adapt to a life entirely disconnected from society and devoid of the amenities of modern living. When finally they were rescued, the family chose to stay in the island – except one son who wanted to study, promising that he would return to the island.

· I write because of similar stories of the same plot such as Robinson Crusoe, a classic novel by Daniel Defoe, and recently, Castaway, a modern version of a lone survivor shown on the screen. We can only imagine what we could have done if we were the survivors ourselves.

· I write to challenge the young generation if such stories have lost their appeal, more so of their relevance. It is as if we have outlived tradition in such a manner that anything which is not modern does not apply any longer. What aggravates it is that as we move in to cities we lose our home base and leave behind much of our native culture.

· I write because I hope to help hold the tide of exodus of people moving into cities, whether in ones own country or abroad, and the lure is so great nearly half of the world’s population is now living in urban centers. Ironically the present population explosion is not being absorbed by the rural areas but by cities, bloating them into megapolises where millions of people as precariously ensconced. And now globalization is bringing us all to one village linked in cyberspace and shrunk in distance by modern transportation. We have indeed entered the age of global homogenization and worldwide acculturation.

· I write to take a good look and compare ourselves with our ancestors from the viewpoint of how life is well lived. Were our ancestors a happier lot? Did they have more time for themselves and their family, and more things to share with their community? Did they live healthier lives? Were they endowed - more than we are - with the good life brought about by the bounty and beauty of nature?

· I write to raise these questions that analyze ten major concerns about living. In the midst of socio-cultural and economic transformation from traditional to modern to globalization - an experience that is sweeping all over the world today - these concerns serve as parameters to know how well we are living with life.

· I write to raise the consciousness of the reader as he goes over the various topics in this book and help him relate these with his own knowledge and experiences, and they way he lives.

· Simple lifestyle

· Environment-friendly

· Peace of mind

· Functional literacy

· Good health and longer active life

· Family and community commitment

· Self-managed time

· Self-employment

· Cooperation (bayanihan) and unity

· Sustainable development

· Eighteen years ago I began to gather and put into writing many things about living. Primarily these are ethnic or indigenous, and certainly there are commonalities with those in other countries, particularly in Asia, albeit of their local versions and adaptations. It leads us to appreciate with wonder the vast richness of cultures shared between and among peoples and countries even in very early times. Ironically modern times have overshadowed tradition, and many of these beliefs and practices have been either lost or forgotten, and even those that have survived are facing endangerment and the possibility of extinction. It is a rare opportunity and privilege to gather and analyze traditional beliefs and practices.

I write for the old folks to whom we owe much gratitude and respect because they are our living link with the past. They are the Homer of Iliad and Odyssey of our times, so to speak. They are the Disciples of Christ’s parables, the Fabulists of Aesop. They are the likes of a certain Ilocano farmer by the name of Juan Magana who recited Biag ni Lam-ang from memory, Mang Vicente Cruz, an herbolario of Bolinao Pangasinan, whom I interviewed about the effectiveness of herbal medicine. It is to people who, in spite of genetic engineering, would still prefer the taste of native chicken and upland rice varieties. It is to these people, and to you in this hall, that this little piece of work is sincerely dedicated.

I would like to read the excerpts of the writings of the critics about my new book.

“Very common people, in very common settings, with very simple objects, now tell us how to keep in touch with nature. For instance we rejoice in the bounty of leafy vegetables growing on discarded tires, sustained with compost from a city dump. We also find relief from a burning fever through a cup of lagundi tea, or savor broiled catfish fattened at a backyard pond. Sometimes, we painfully ponder the fate of a dog headed for slaughter, or grieve at the gnarled skeleton of a dead tree, or awe in at the metamorphosis of a cicada, or immersed in the lilting laughter of children at play.”

Anselmo S. Cabigan, Ph.D.

Professor Ronel P. dela Cruz, Ph.D.

Professor, St. Paul University Quezon City

No comments:

Post a Comment