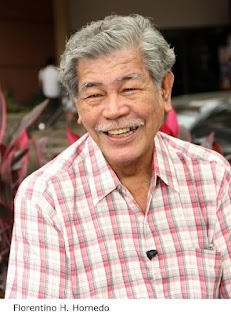

In memory of the late Dr. Florentino H. Hornedo

"The Visitor and the Native in the Jeepney and the Tricycle"

By Dr. Florentino H. Hornedo

Professor UST Graduate School

UNESCO Commissioner

The

Anthropologist Frank Lynch S.J., after years of careful observation of natural

and cultural patterns in Philippine history, concluded: “Today’s native is

yesterday’s visitor.” In today’s continuing definition of what is called

“Filipino Identity”, it may be time to see what Fr. Lynch saw and what many

have since began to consider – the nativization of the visitor. I myself wish

to illustrate this process by the ubiquitous jeepney and the tricycle.

The Willys jeep acme came as a visitor some fifty years

ago. It was a durable short vehicle that could, with some effort, accommodate

some half dozen persons. Then the Filipino got hold of this raw material and

created something very different. The four wheels are still there, but it is no

longer as short as the original. It is still a passenger vehicle, but it can

now load – if not in theory, at the very least in fact – some three dozen

people (PHOTO). It has lost its canvas up and now sports a roof nearly inspired by the

turtle’s shell. It can have windows that look more like domestic windows

complete with curtains and colored jalousies made of glass or plastic. Its

dashboard now carries a portable altar that makes of the vehicle a mobile

chapel of sorts. And its windshield has became a veritable billboard for humorous

stickers as well as political and religious statements.

Whatever engineering went into the design of its seat has

declared itself independent of the matter of convenience, comfort and security

for the users. The number of passengers is determined not by Filipino

philosophy not the laws of physics but by the driver’s calculation of how many

can fit within unreasonable limits, and assure him the most fare for his trip.

On the hood, the memory of rural cockfight is memorialized by metallic roosters

caught in their gloriously futile attempt to win over an absent opponent.

Similarly, miniature racehorses might bounce to and fro

on their spring base, while nearly a dozen mirrors face a single direction for

no one’s particular benefits. In the days when the law did not prohibit radios

and the jeepney was a mobile jukebox, it had antennae tall enough to serve as

transmitting tower, ornamented with bunting and frill in rainbow colors. When

the law attempted to get rid of the radio, the antenna remained in useless memory

of lost function.

Generation

of public transportation administration have attempted to assassinate this

durable creation and technology has modified its regal design to the vulgarity

of the Fierra and the old Tamaraw – both to no avail. In many

instances, the elegantly carved glass mirrors with lines inspired by art deco

and baroque have completely bowed out in favor of nondescript mirrors which

serve little else than give the illusion of spaciousness.

The jeepney is also not above masquerading as a cargo

truck, loading cavans of rice and crates of fruits to the unpredictable

consternation or delight of commuters who, accordingly sit themselves on the

jeepney’s hood or when possible, its roof.

A more recent visitor is the Honda motorcycle from Japan.

It came on two wheels and was a good for two passengers. The Filipino took it

in and regurgitated it as a tricycle (PHOTO) which in its more desperate and felicitous

moments, can carry eight people. Here the laws of mechanics and physics are

suspended by a cultural sort of hocus pocus that works. The Filipino genius at

work has made a clear distinction between comfort and transport. While in other

matters such as food, the Filipino loves mix-ups divinely, in this kind of

vehicular dispensation, he becomes strictly enamored of a clear distinction: if

you want comfort keep out and buy yourself a car. But if you want transport, be

ready to be retreated as an ordinary cargo! The tricycle has become a

legitimate purveyor of oral tradition and criticism, as well as a veritable

vent for the little and many frustrations of daily life voiced through graffiti

and stickers which say no in uncertain terms what the driver damn wishes to

say, if to no one else, then at leave to himself.

A more recent visitor is the Honda motorcycle from Japan.

It came on two wheels and was a good for two passengers. The Filipino took it

in and regurgitated it as a tricycle (PHOTO) which in its more desperate and felicitous

moments, can carry eight people. Here the laws of mechanics and physics are

suspended by a cultural sort of hocus pocus that works. The Filipino genius at

work has made a clear distinction between comfort and transport. While in other

matters such as food, the Filipino loves mix-ups divinely, in this kind of

vehicular dispensation, he becomes strictly enamored of a clear distinction: if

you want comfort keep out and buy yourself a car. But if you want transport, be

ready to be retreated as an ordinary cargo! The tricycle has become a

legitimate purveyor of oral tradition and criticism, as well as a veritable

vent for the little and many frustrations of daily life voiced through graffiti

and stickers which say no in uncertain terms what the driver damn wishes to

say, if to no one else, then at leave to himself.

The logic if this method of defining cultural identity is

the evidence arithmetic of the subtrahend and the remainder. Take away from the

present jeepney and tricycle those things that were in their original form as

visitors – the Willys and the Honda – and what is left is what we can call

Filipino, our contribution, our identifier.

After the subtraction of course, these creation will not

ruin since the engines too are visitors. But there is such thing for the

Filipino as appropriation by extended possession – the metaphysical ground for

the philosophy of squattership. And maybe, in this sense, the imported engine

becomes Filipino and naturalized by extended possession and/or association.

It is clear from the foregoing that the logic of the

definition of Filipinicity transcends the arithmetic of the subtrahend and the

remainder. There is a minuend that refuses to be reduced by simple subtraction

of the visitor from it in order to arrive at the identity of the remainder. The

minuend has arrogated unto itself a kind of wholeness and identity which

combine the foreign raw material with local contribution in a manner that is

less mechanical – the way an appendage becomes conjoined with another to

produce nothing more than appendages – and more organic and assimilative – the

way food becomes a constitutive part of the eater. The Filipino addition to the

jeep and the tricycle is not an appendage but an identity, a habitation and a

name. The metamorphoses s a growth, an adaption to environment, a response to a

need which the original creator of the raw material did not know nor

appreciate. What has happened is what happens to muscovado when it is transmuted into a rainbow-colored candy stick, or what happens to the tubes of

paint when they are transformed into works of art. What happens in the

transition is a creative event and the result is a persona.

The Filipino has, for ages, been on the receiving end of

things foreign, in terms of both goods and needs. Among the goods have been the

jeep and the motorcycle and among the needs have been mobility and convenience.

When one adds to these the need to maximize within very limited means in order

to meet the demands of a large and growing population, the result is the

synthesis of a minimal, borrowed, raw material and a craftsmanship desirous of

maximal utility. That explains the enlargement of the jeepney and the addition

of one more wheel and a passenger compartment to the tricycle. It is a

technological translation of the Filipino proverbs. “Mamaluktot habang angkumot ay maigsi.” (Crouch if your blanket is

short.)

But the Filipino also brings in his cultural and

individual personality into the new vehicle. In his traditional transport

-- the kalesa (PHOTO), the carabao or ox-drawn cart, or the back of the carabao,

he is ferrying either townmates or member of his own family as they return from

the farms. In this traditional transport system, personalism is a factor which

makes trips both social and satisfying. One can talk at leisure about familiar

matters and mutual concerns. The driver is not an outsider not a stranger. He

may even be the head of his family, and to play a role in the cart as the

driver is really to play all over his role in his house as father and family

head. The cart is a kind of home, and the kalesa

is a kind of social venue, and in both cases the marks of home and native

social community make the technological object familiar and psychologically

satisfying.

But the jeepney and the tricycle answer a different kind

of need. More people must be transported and at the shortest possible time.

There is no time for social conversation nor is it possible at all due to the

impersonality of the big crowd which rides in order to rush to work or to the

market and not to socialize. It is now understandable why the driver must

create for himself within the vehicle the permanent substitutes for a vanished

social and familial function.

Bullock drawn bridal cart

The traditional features of his society and the

personalized characteristics of home must accompany him come hell or high

water. The wife’s embroidery and tasselled drapery must be there. Icons of

favourite religious patrons are enthroned on the dashboard as they are in the

family altar. His drinking partners and their punning jokes often off color,

are there, too. “ipitin pa lamang nang

magkahusto!” “Jeepney driver, short

time loser.” God knows Hudas not pay.” Or,

to tell the world that this jeepney was bought with hard-earned money

from Saudi Arabia, he hangs a sign below the back entrance.”Katas ng Saudi.” Or if he wishes to

laugh at the foiblesof a poor world, he less his ticket do the work: “inay, sino po ang tatay ko! Ewan, marami

sila.”

Graffiti of this sort are also attempts to speak to the passengers

and lesson the growing impersonalism in the environment. They are psychological

coping mechanisms produced by a social spirit forced into an increasingly

depersonalized world. Filipinizing is the process of exorcising the alienness

of the borrowed technology by bringing into it the familiar and social marks

and features of Filipinicity, thus giving the new creation a familiarity a

habitation and a name. it involves the enviness right of the free to name the

world they create.

The creative adoption of the “visitor” in order to make

it a naïve is an assertion of creative freedom. It is an affirmation of both

interdependence and independence of spirit. This I hold to be as true to the

transformed vehicles as to so much of other features of Filipino art, sciences

ad technologies, which ones came to the country as visitors. And the miracle is

that transformation is probability one form of native hospitality, which is the

one thing we are never short of nor without. ~

------------

Posted by Dr Abe V Rotor in his honor and in recognition for being an outstanding Filipino educator and social scientist.

No comments:

Post a Comment